Designers can empower people to make confident decisions. Empowerment goes beyond just basic functionality: we help people meet their needs and gain a sense of fulfillment and knowledge through their interactions with screens, products, and services. Empowerment is the sense of confidence people gain by making decisions and feeling good about the decisions they make. Our users take that feeling into other interactions as well.

Empowerment is at the core of trust, too. Today, cynicism undermines trust in the media, government, public health, and consumer brands; just ask any organization that teaches, persuades, or engages users through its services or products. To regain the trust of consumers and citizens, we talk about empathy and transparency—but we need to design differently too. By offering a consistent visual and verbal voice, the appropriate volume of information, and vulnerable audience engagement, we can help organizations regain trust and help our users make better choices, self-educate, and engage the world with greater confidence.

In this excerpt from Trustworthy: How the Smartest Brands Beat Cynicism and Bridge the Trust Gap, Margot Bloomstein explores the role of abstraction in presenting information to inform decisions. Sometimes, more isn’t better—it’s just more, and it’s overwhelming. We can help people navigate that stress. And what better time than amid a pandemic to bring this skill to the table?

Balance fidelity and abstraction to inform beyond the facts

“Just because you’re accurate doesn’t mean you’re interesting,” jokes comedian John Mulaney in his special Kid Gorgeous.1 He’s talking about the irrelevance of distracting details, but his statement is a lesson to anyone trying to motivate their audience to act on information. Sometimes, you simplify details so that people can get the big picture. What concepts stand out as faithful to the original? That’s abstraction: the process by which you transform information to simplify and translate it while remaining true to the original concepts.

Abstraction helps organizations move beyond overwhelming details to more actionable and trustworthy information. Sometimes the information you have needs to be changed into a new format or context. Sometimes it’s too detailed to be useful, or it focuses on the wrong details; it’s accurate, but not interesting, as Mulaney says. In other cases, people can’t relate to the specific case to understand how it applies to them. Good advice is buried in irrelevant back story. Let’s explore how abstraction helps us communicate the truth with fidelity. Fidelity is the degree to which a new version reflects reality.

Do you simplify the story and leave out some details to get to the important part and retain readers? Do you shift the context to make examples more relatable and help the audience empathize? Or do you reframe details in a more familiar format, all to control the message and ensure the audience isn’t distracted by the noise? Actionable communication empowers people by filtering the real world. As a designer, writer, or marketer you can provide users with the power to act with confidence. By abstracting reality, we make the essential information more actionable, useful, and personally relevant. That kind of utility is the most basic level of information design, whether your users are navigating a disease treatment plan, a ballot, or a map. By finding a balance between telling the truth and omitting unnecessary noise, you empower your audience with information that’s both more useful and usable, and worthy of their trust.

“What is believed overpowers the truth,” wrote Sophocles.2 Today, perhaps, it’s more accurate to say that what is believed is the truth. Truth is a personal thing shaped by experience and perception, but belief and truth stand separately from reality. Design is a helpful intermediary between reality and truth.

All these things are true even if they didn’t happen

Abstraction allows us to act with confidence and without overthinking the details. Sometimes, writers and designers can streamline the details or condense the nuances, all in the name of serving a greater good: actionable understanding. Think about maps. Sometimes, they gloss over reality to deliver the truth.

“All maps are useful lies,” offers Stanford design instructor [and founder of Boxes and Arrows] Christina Wodtke. “A map’s job is to help someone go from one place to another place. But if your map shows each restaurant, driveway, and side road accurately, it becomes so dense that you can’t navigate with it.” An overly detailed map won’t be useful. So, maps omit details that the artist—or user, if the map is interactive—deems irrelevant. The driveways and side roads still exist; they just aren’t shown. In some cases, details are exaggerated to reflect importance. In other cases, the cartographer changes relationships to serve a greater purpose: the map doesn’t just need to be useful, but it needs to be usable—memorable, even. It needs to fit the user’s mental model.

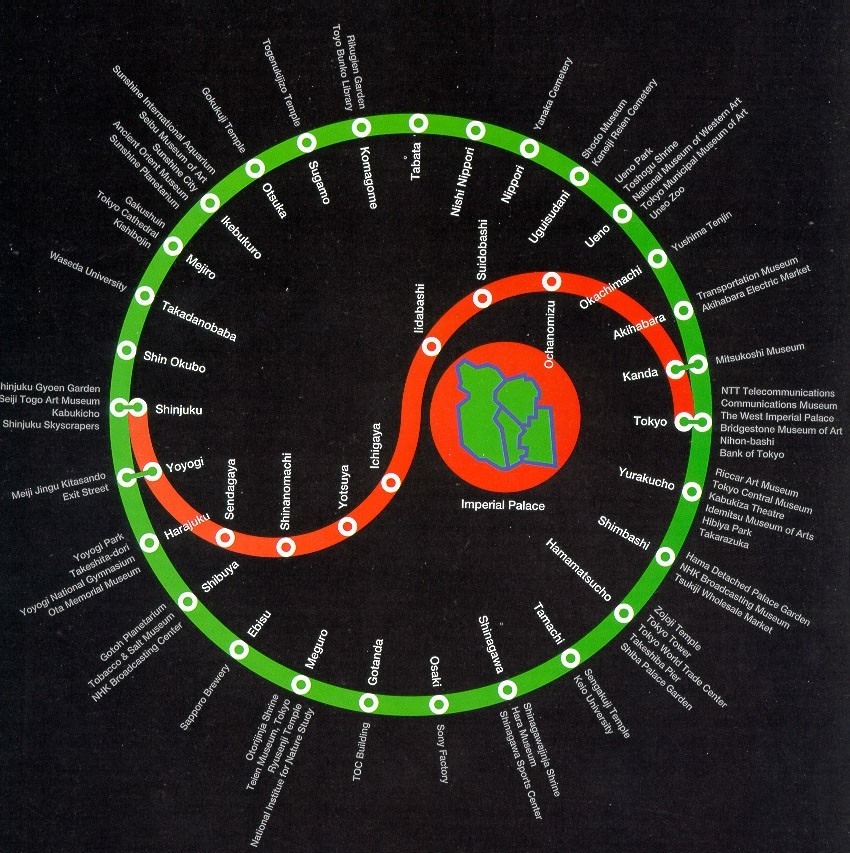

Information architecture pioneer Richard Saul Wurman designed a map3 of two major Tokyo subway lines that crisply contrasts against models that are more representative. Like in standard maps of the city’s transit system, the circular Yamanote Line rings the city and the Chūō-Sōbu Line bisects the ring. There’s a jog in the middle, with the lines shifting further north as they go east. But Wurman smooths the turns—committing lies of omission—and broadens the ring. His map is usable, though it’s not realistic. But do these changes matter on a map? “Underground, you don’t need to know every turn,” comments Christina. “They don’t matter. Instead, Wurman made a concept model of the subway based on a yin-yang. When people familiar with a yin-yang see his map, they update their mental model of the subway system.” Wurman’s choices matter because his model helps visitors remember the relationships between stations and learn approximate distances, contributing to their confidence and trust that they can get around.

But models are not without their baggage. As communication theorist Paul Watzlawick4 noted, we cannot not communicate. To western tourists, the model may be helpful—but to others, the yin-yang as a graphic element, divorced from its meaning of dualism, just feels like reductive, clichéd orientalism.

“Mental models help people remember and attain new information,” continues Christina. That process is vital for giving people ownership over their learning and confidence in their own ability to self-educate.

When we abstract ideas to aid attention, comprehension, and retention—the process of learning that Christina describes as her “teaching trifecta”—those ideas have more impact. We remove the friction of unnecessary details and sticking points. If TED champions “ideas worth spreading,” abstraction and simplification enable that spread. “Look at info memes,” says Christina. “They’re models so small and easy to draw that they can travel. They’re simple enough that when you’re talking to your boss, you can grab a whiteboard marker and throw it up there.” These concepts are so simple that they can be sketched and passed on without losing information.

Map design offers a compelling example of the ethics of abstraction that span the distance between a daunting, overly detailed reality and an actionable truth. Sometimes information is too detailed to be actionable.

“Information anxiety is the black hole between data and knowledge, and it happens when information doesn’t tell us what we want or need to know,” wrote Wurman.5 Maps help reduce that anxiety for some people. They tell us where we are, where we can go, and how to get there. Maps abstract reality by sacrificing some detail to be more useful. That tradeoff reduces anxiety, the killer of confidence. But is that enough to inspire confidence in the source of information and, ultimately, to inspire trust?

Offer enough detail to be plausible but leave space to be relatable

Abstraction offers another benefit: by sacrificing detail, the essence of your message becomes plausible, believable, and relatable. Good storytellers value being believable: they give us enough detail to see what they mean, but ensure that those details are relatable enough to be relevant to the audience. The empathy of shared experience orients us and fills the space between the storyteller’s narrative and how we relate it to our own adventures in the world. “Stories are good audio maps,” says Christina Wodtke. They focus your attention, facilitate comprehension, and aid retention—or our ability to organize new information into the concepts we already grasp. At the most basic level, metaphors work in the same way: they offer a shorthand mental model that anyone can relate to their own experiences and things they already know. “The project was a rollercoaster” conveys the abrupt highs and lows of an assignment, even though the team never set foot in an amusement park. “That presentation was a slog” calls to mind trudging through a muddy hike or slushy winter sidewalk, even though everyone sat through it without getting out of their seats. Fidelity to the details matters far less than the point: that presentation was tiring, arduous, and took forever! You’re lucky you didn’t have to sit through it.

When you cut distracting details, empathy fills that gap—but empathy is more than a byproduct of minimalist design or concise writing. It’s a core product—and a Trojan horse for trust. By allowing space for the audience to overlay their own memories on a story or image, you make the information more valuable to them, because now it’s more relevant. Realtors apply this method when they stage a home, leaving a few inviting landscape paintings but hiding the personal vacation photos. They keep the details that illustrate specific common experiences, but cut the bits that prevent prospective buyers from seeing themselves in the space. Moreover, they retain the décor and furniture that hints at relatable lifestyle aspirations and adequate storage.

Abstraction is different from generalizing. Don’t cut the details that convey central concepts and core truths, or there won’t be anything that the audience can relate to their own lives. While illustrations and stories are no substitute for data, they help us connect with bigger concepts. Those concepts can feel familiar if they relate to our own experiences, and it feels safe to build new knowledge on familiar concepts. We use data, but we trust humans. By sharing enough specific detail, you can ground the truth and key takeaways in concepts familiar enough to encourage your audience’s trust and interest.

When imagery or content focuses too much on the wrong details, viewers lose the bigger concepts. Airbnb’s early work with video tours offered too much detail. They painstakingly gathered all the features visitors look for in search queries—hairdryer! laundry on site!—and went overboard showing each of these details, which could have come through just as well in bulleted lists. Video tours were well produced, but it was too much. Their professional polish and scripted content made them informative—but they didn’t feel authentic.

“Our early videos were minute-long stories that reflected common search queries,” explains Shawn Sprockett, a former design lead at Airbnb. “They were beautifully shot and well produced—but the way they answered questions looked like marketing.” The scripted, anticipatory manner of fully explaining house listings proactively answered questions for prospective guests, but the videos came on too hard. “They made the listings look less authentic,” he adds. Rather than looking like the work of real people showing off their apartments or vacation rentals, the videos looked and sounded slick. They were driven by search engine terms, not property owners’ passion for their town or pride in a newly remodeled kitchen. All that polished content overwhelmed potential guests and property owners and put them in a defensive mindset, pushing them to move on to other listings and other rental sites.

“The next version of those videos looked more real,” he continues. The hosts focused on the details they thought were important and filmed without format guidelines or keyword lists from Airbnb. “No more scripting—we had people just answer questions in their own words.” Gone was the professional camerawork, or at least the qualities that hinted at it. Instead of reminding hosts to film with the camera in a horizontal orientation, they let them hold the camera or phone vertically, the default for most people who don’t have a background in photography. “We rotated from horizontal cinematic filming to vertical, like Snapchat,” he says. That change might make some photographers cringe, but it speaks the language of people who aren’t professionals and just want to grab a snapshot or shoot a quick video. It’s more relatable and authentic. “Authenticity builds trust, and we don’t want to undercut our own goals,” Shawn notes. The details that came through revealed more of the hosts’ passion and less of user search queries.

The simple change of switching from horizontal to vertical in the videos signaled that the values of the person (or brand) making the video may be more aligned with the values of visitors who don’t care about such details, or are more attuned to Snapchat than to professional videography. By focusing attention elsewhere and seemingly letting those details slip through the cracks, Airbnb affects a younger, more digital-native-friendly posture. Here, authenticity builds on a carefully studied apathy.

“We never intentionally made anything look bad,” cautions Shawn. “But we realized that something that looks great to a designer could just get in the way.” By considering the finer points in camerawork and content creation, Airbnb created something more accessible and useful to a potential guest.

One of Airbnb’s central motivations is to help travelers connect more meaningfully with their destinations. If you’re looking outside of standard, generic hotel chains for something more authentic, a homestay through Airbnb offers interaction with local hosts and the comfort of a home. By focusing on details like video that maintains the voice and style of hosts, Airbnb ensures that their production style doesn’t distract from the main points of their value proposition to visitors.

1 Scraps from the Loft, “John Mulaney: Kid Gorgeous at Radio City (2018)–Full Transcript,” May 5, 2018, http://scrapsfromtheloft.com/2018/05/05/john-mulaney-kid-gorgeous-at-radio-cityfull-transcript.

2 Sententiae Antiquae, “What Is Believed Overpowers the Truth: Sophoklean Fragments on Lies and Truth,” June 23, 2015, https://sententiaeantiquae.com/2015/06/23/what-is-believed-overpowers-the-truth-sophoklean-fragments-on-lies-and-truth.

3 Richard Saul Wurman, Tokyo Access (Los Angeles: Access Press, 1984).

4 Paul Watzlawick, Janet Beavin Bavelas, and Don D. Jackson, Pragmatics of Human Communication: A Study of International Patterns, Pathologies, and Paradoxes (New York: W.W. Norton, 1967).

5 Richard Saul Wurman, Information Anxiety (New York: Doubleday, 1989).

Post a Comment